Combining dairy and plant proteins in cultured products, like yogurt, creates unique challenges and opportunities for product developers, balancing technical aspects such as protein digestibility, texture, taste, and stability. While dairy proteins offer high digestibility and consistent gelling properties, plant-based proteins require specific formulation techniques due to their lower solubility and distinctive flavors; however, blending these protein sources can provide the best of both worlds, delivering products with improved environmental impact, enhanced fiber content, and a more flexible flavor profile. The following article was first published on GlobalFoodForums.com

Combining Dairy and Plant Proteins in Cultured Products

Plant-based products are often positioned as replacements for their dairy competitors. However, “What if, rather than having to choose one or the other, you could get both benefits in one?” asked Hillary Sandrock, Senior Scientist with Merlin Development. Sandrock posed the question during her presentation, “The Best of Both Worlds: Combining Dairy & Plant Proteins in Cultured Products,” at Global Food Forums’ 2022 Protein Trends & Technologies Seminar.

Yogurt starts with milk, a natural product with a PDCAAS of 1.00 and a DIAAS of 1.14. Yogurt production involves blending, pasteurizing, homogenization, and fermentation. Yogurt cultures feed on lactose and produce lactic acid, which drops the pH to 4.6, where casein aggregates and forms a gel network.

To make plant-based yogurt, start with plant protein, which can come from various sources, including legumes, cereals, and nuts. Plant proteins tend to have a globular structure, like whey. They are generally less digestible and have lower solubility than dairy proteins, and they possess characteristic plant protein flavors, Sandrock explained.

Creating Plant-Based Milk Products

Creating plant milk could involve hydrating a protein powder or soaking, grinding, and milling a nut. Fats and oils are added to produce the desired fat content, and a carbohydrate source, such as glucose or sucrose, is added. Starches and gums are used to stabilize and provide thickening and texture. Culture times are generally longer. The finished product often has a higher solids nonfat (SNF) level.

Plant source candidates for yogurt include those in the top-selling plant-based milks—almond, oat, soy and coconut. Coconut is a popular yogurt base, but coconut yogurts contain less than 1% protein compared to 3 to 5 % protein for dairy yogurt, Sandrock pointed out.

Soy has a PDCAAS of 0.98 and a DIAAS of 0.90, is relatively neutral in color, and has some gelling properties. However, soy is a major allergen known for its beany flavor and astringency in acid conditions.

Oats contain 10 to 15% protein and are high in soluble fiber. Their beta-glucans and starches contribute to a slimy texture in yogurt. To reach a target protein level, combine oat with chickpea, advised Sandrock. Chickpea is a legume like soy but with less protein. Chickpeas are not a major allergen, contribute fiber, and have natural emulsifying properties. However, they too can contribute off-flavors.

Almonds have a sweet, nutty flavor and good gelling properties. They are also a significant allergen. Almonds have a PDCAAS of 0.29 and a DIAAS of 0.40. They contribute healthy fat and generally produce a higher fat yogurt.

Why Not More Plant-based Yogurt Consumption?

The number one reason people don’t choose plant-based yogurt is because of its taste. High cost is also a concern, as is texture.

Does it make sense to combine plant-based and dairy yogurts? We have seen a lot of growth in plant-based yogurt sales in the last few years, but it’s a small fraction of the dairy yogurt market. Sandrock noted that about half of U.S. consumers embrace the flexitarian lifestyle, while only 6% identify as vegetarian or vegan. However, nine out of 10 consumers of dairy alternatives also eat real dairy.

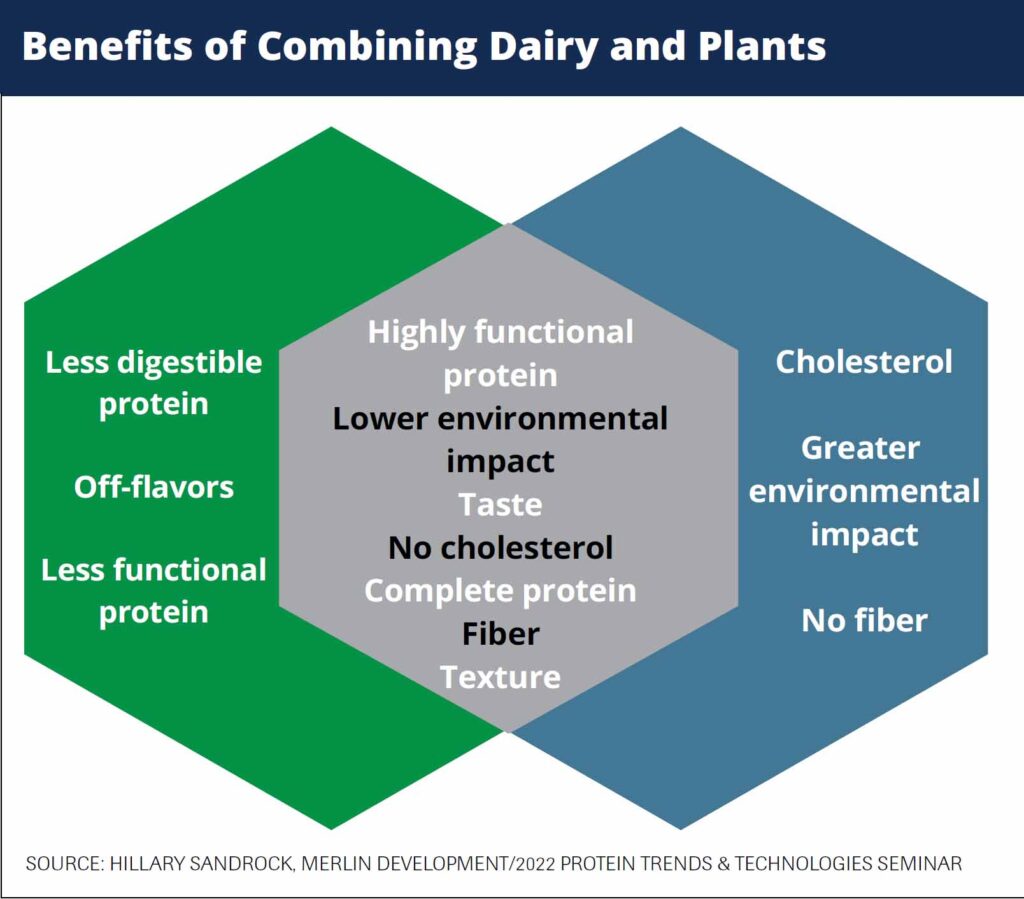

Plant-based and dairy yogurt have advantages and disadvantages. Combining dairy and plant proteins can achieve a highly functional protein blend with a lower environmental impact, good taste, no cholesterol, complete protein, a fiber claim, and good texture.

Plant-based and dairy yogurt have advantages and disadvantages. Combining dairy and plant proteins can achieve a highly functional protein blend with a lower environmental impact, good taste, no cholesterol, complete protein, a fiber claim, and good texture.At Merlin Development, a sensory panel compared yogurts of varying dairy- and plant-based protein blends. They chose four different retail plain yogurts—dairy, almond, soy, and overall liking at different blended ratios.

- ALMOND: Blends with higher levels of almond yogurt were more beige, thicker, and had a higher viscosity. Almond-based yogurts were quite sweet with increased nuttiness.

- SOY: Lower levels of soy in dairy/soy blends scored remarkably similar to all-dairy yogurt in most attributes except the color. Blending soy into dairy also created increased chalkiness and “beaniness.”

- OAT/CHICKPEA: In the oat/chickpea blends, chalkiness increased with the percentage of plant-based yogurt. The cereal and cardboard notes were more prevalent in these blends at higher blend levels.

A compilation of results from scientific journals revealed that plant yogurts generally scored below five on a nine-point Hedonic scale in texture, flavor, and overall liking. Some 53% of consumers said that taste is a significant barrier to eating plant-based yogurt. Merlin Development panelists saw similar trends. Except for almond, all 100% plant-based yogurts were disliked. Various blends of dairy- and plant-based yogurts achieved acceptable liking scores.

When comparing the nutritional values of the various blends, all samples had similar protein levels, comparable to dairy yogurt. Carb levels were higher with all the dairy/plant blends. The almond yogurt blends had a considerable spike in fat, but saturated fat was less than dairy-based yogurts. Dairy has no fiber, but all blended yogurts achieved a fiber claim.

Caption of chart: Plant-based and dairy yogurt have advantages and disadvantages. Combining dairy and plant proteins can achieve a highly functional protein blend with a lower environmental impact, good taste, no cholesterol, complete protein, a fiber claim, and good texture.

Click on the phrases below to see related articles on these topics at FoodTrendsNTech.com.